Philadelphia

The largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the second-most populous in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, Philadelphia is a city of considerable historical significance since it served as the nation’s capital until 1800. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,603,797. It is co-extensive with Philadelphia County, which is the most populous county in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia is part of a larger metropolitan region, the Delaware Valley, which has 6.245 million residents in the metropolitan statistical area and 7.366 million in its combined statistical area. Notable contributions to American history, culture, sports, and music have been made by Philadelphia.

LISTEN TO RADIO PGH – THE REVOLUTION HAS BEGUN!

History of Philadelphia

In 1682, William Penn established the city of Philadelphia in the English Crown Province of Pennsylvania, located between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, previously inhabited by the Lenape people. It rapidly developed into a prominent colonial city and was the setting of the First and Second Continental Congresses during the American Revolution. The federal and state governments subsequently relocated, though Philadelphia remained the financial and cultural hub of the United States. By the start of the 19th century, the city had become a major industrial city, with textiles as the leading industry.

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, Philadelphia was under the rule of a Republican political machine, and was labeled as “corrupt and contented” by the beginning of the 20th century. Through various reform measures, the most prominent of which was the 1950 city charter, the power of the mayor was reinforced, while the Philadelphia City Council was weakened. At the same time, the city shifted its allegiances from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party, which has since developed a strong Democratic organization.

Beginning in the 1950s, Philadelphia saw a decrease in population as many white and middle-class families moved away to the suburbs. This was due to many of the city’s houses being in disrepair and the presence of gang and mafia violence. In the 1990s and early 2000s, however, revitalization and gentrification of neighborhoods began to bring people back. Incentives implemented at this time also helped improve the city’s image and caused a condominium boom in Center City and the surrounding area, helping to slow the population decline.

Philadelphia’s Past

During the 1700s

Prior to Europeans colonizing Philadelphia, the Lenape (Delaware) Indians occupied the Delaware River Valley. This area was known as Zuyd, indicating “South” River, or L enapei Sipu.

The Lenape settlement of Coaquannock, meaning “grove of pines,” was located north of the site that would later become Center City and on the east bank of the Schuylkill. One of the largest Lenape settlements in the region, known as Passyunk, meaning “in the valley,” was situated in today’s South Philadelphia near the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers. Other settlements, such as Nitapekunk, meaning “place that is easy to get to,” located in the Fairmount Park area, and Shackamaxon, meaning “place where the chief was crowned,” were on the west bank of the Delaware River, upstream from present-day Northern Liberties.

In 1609, Henry Hudson and a Dutch crew ventured into the Delaware River Valley whilst looking for the Northwest Passage, thus making the area part of the New Netherland Dutch claim. During the 1630s, the Dutch wanted to gain control of the Great Minquas Path, a fur trading route to the Susquehannock which passed through the Philadelphia region, so they constructed a palisaded factorij near the Schuylkill River and Delaware River junction, named Fort Beversreede.

In 1637, the formation of the New Sweden Company was initiated by stockholders from Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany. This company was formed to trade for furs and tobacco in North America. Peter Minuit, who had served as the governor of the New Netherland from 1626 to 1631, was the leader of this expedition. The two ships, the Kalmar Nyckel and the Fogel Gri, left Sweden and reached Delaware Bay in March 1638. The settlers began to build a fort there, which they named Fort Christina in honor of twelve-year-old Queen Christina of Sweden. This settlement was the first permanent European colony in the Delaware Valley. Part of this territory included land on the western side of the Delaware River, extending from the Schuylkill River downward.

In 1642, George Lamberton, at the head of 50 Puritan families from the New Haven Colony in Connecticut, attempted to set up a theocracy by the Schuylkill River. The Lenape had previously made a deal with the New Haven Colony to acquire a significant portion of New Jersey south of Trenton. The Dutch and Swedes in the region burned the buildings of the English colonists, and a Swedish court led by Johan Bjornsson Printz accused Lamberton of trespassing and conspiring with the Indians. The colony of New Haven didn’t get any help and Governor John Winthrop declared it dissolved due to the summer sickness and mortality. This event resulted in New Haven losing control of its region to the Connecticut Colony.

On February 15, 1643, Johan Bjornsson Printz was selected to be the first governor of New Sweden. During his decade-long reign, the capital was moved to Tinicum Island, which today is located near the city of Philadelphia. There, Printz established Fort New Gothenburg and a personal estate which he named the Printzhof.

In 1644, the Swedes of New Sweden aided the Susquehannock in their successful confrontation with General Harrison II and the Maryland colonists. This collaboration was meant to further their claims for land near the Schuylkill River. So, New Sweden constructed a blockhouse that was 30-by-20-feet right in front of the Dutch Fort Beversreede, which they named Fort Nya Korsholm or Fort New Korsholm. This building was only 12 feet away from the entrance of the Dutch fort in an attempt to repress the Dutch and check trade. This prompted the Dutch to abandon Fort Beversreede in 1651, and they relocated Fort Nassau to the Christina River, lower than Fort Christina. In the end, the Dutch merged their forces at the renewed Fort Casimir.

In the summer of 1655, Peter Stuyvesant of New Amsterdam organized an expedition to the Delaware Valley in order to take control of the Swedish colony that had not been recognized officially by the Dutch. Although the settlers were obligated to accept New Netherland’s authority, they still had a lot of liberties such as their own militia, religion, court, and lands. This situation remained unchanged until the English seized New Netherland in October 1664, and was still in effect even after the area became part of William Penn’s charter for Pennsylvania in 1682.

The Swedish immigration into the Philadelphia area continued in 1669 with the arrival of Sven Gunnarsson. He established himself at Wicaco, a former Native American settlement and constructed a log blockhouse. Five years prior to the formation of Philadelphia, the Swedish congregation of Tinicum Island relocated to Wicaco and utilized the blockhouse as their church. Gunnarsson passed in 1678, and was among the first to be interred at the church grounds. This became the Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) Church, the oldest church in Pennsylvania.

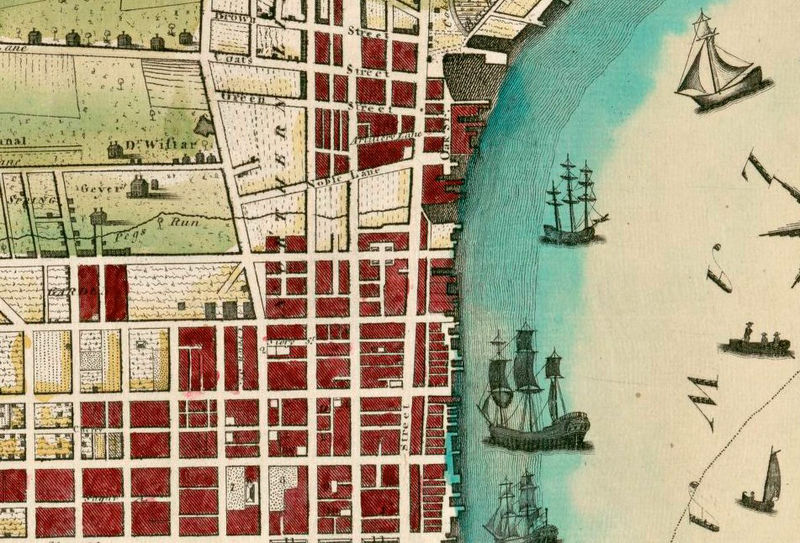

William Penn, a Quaker, had the vision of a place where people of all religious backgrounds could live and worship without fear of persecution. To achieve this, he laid out the streets of the city in a grid pattern, aiming to create a city more reminiscent of the smaller towns of England than its more crowded metropolitan areas. The first buyers were granted land on the Delaware River for their homes and the city was given access to Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, making it a prime port in the Thirteen Colonies. He named the city Philadelphia, derived from two Greek words meaning “love” and “brother”. The grid plan was modified from one designed by Richard Newcourt for London.

William Penn dispatched three agents to manage the arrangement and set aside 10,000 acres (40 km2) for the city. They got the land from natives at the settlement of Wicaco, and from there started to outline the city northward. The range was about a mile along the Delaware River between today’s South and Vine Streets. Penn’s vessel dropped anchor off the coast of New Castle, Delaware on October 27, 1682, and he arrived in Philadelphia a few days after that. He stretched the city west to the bank of the Schuylkill River, with a total area of 1,200 acres (4.8 km2). Streets were organized in a gridiron pattern. Apart from the two broadest roads, High (now Market) and Broad, the streets were named after prominent landowners who owned adjacent plots. The streets were renamed in 1684; those running east-west were named after local trees (Vine, Sassafras, Mulberry, Cherry, Chestnut, Walnut, Locust, Spruce, Pine, Lombard, and Cedar) and the north-south streets were numbered. Inside the territory, four parks (now known as Rittenhouse, Logan, Washington and Franklin) were designated to be open to everyone. Penn designed a central square at the crossing of Broad and what is now Market Street to be encircled by public buildings.

The initial inhabitants of the area were housed in caves hewn out of the river bank. However, the city developed due to the building of dwellings, religious institutions, and wharves. Unlike Penn’s aspirations of a sparsely populated city, the proprietors opted to buy land along the Delaware River rather than extending to the Schuylkill. These lots were divided into smaller parcels and sold, with roads being built between them. Before 1704, there were very few individuals living farther than Fourth Street.

In 1683, Philadelphia had only a few hundred European inhabitants but this number had grown to 2,500 by 1701. This population consisted of people from various European countries, including England, Wales, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Finland, and the Netherlands. Before his last departure from Philadelphia on October 25, 1701, William Penn issued the Charter of 1701, which established the city as such and granted the mayor, aldermen, and councilmen the authority to create laws, ordinances, as well as regulate markets and fairs. The first Jewish inhabitant of Philadelphia was Jonas Aaron, a German, who moved to the city in 1703. This was stated in an article entitled “A Philadelphia Business Directory of 1703” by Charles H. Browning, which was published in the American Historical Register in April 1895.

In 1681, Charles II gave a large tract of his newly obtained American land to Admiral Sir William Penn, the father of Penn, to satisfy a debt. This property included present-day Pennsylvania and Delaware, although the legal rights of the land sparked a disagreement with Maryland, referred to as Cresap’s War. Penn established a colonial expedition and fleet that departed for America the following summer. Penn first set foot on the colony of New Castle, Delaware. The inhabitants of the area pledged loyalty to Penn as their new Proprietor and the first Pennsylvania General Assembly was soon convened in the settlement.

Around 1682, roughly fifty Europeans, the majority of whom were subsistence farmers, had settled in and around the Wicaco area, which is now the location of Philadelphia.

William Penn’s journey up the river culminated in the founding of Philadelphia, which was populated by a core group of Quakers and other individuals seeking religious freedom. This period of colonization was characterized by peaceful cooperation with the Lenape or Delaware nation, in contrast to the conflicts between the tribe and the Swedish and Dutch settlers. In time, Quaker and Anabaptist, Lutheran and Moravian colonists ventured up the Schuylkill and down the Susquehanna River, where they were met with hostility from the Conestoga peoples. Meanwhile, the Province of Maryland had just finished their declared war against the Susquehanna and the Dutch, who had been trading for firearms and tools. Relations between the Delaware, Iroquois, Dutch, Swedish, and English settlers were strained, as Penn’s Quaker government was not well-received. Consequently, the settlers in what is now Delaware soon began demanding their own Assembly.

Philadelphia in the 18th Century

The city of Philadelphia quickly became a major trading port and a very important center. At first, the main type of trade that was conducted in the city was with the West Indies, which took part in the Triangle Trade involving Africa, Europe, and the West Indies. The Queen Anne’s War of 1702 and 1713 interfered with the city’s trade with the West Indies, causing financial damage to Philadelphia. Once the war concluded, it brought a momentary prosperity to all of the British territories, but this was followed by an economic depression in the 1720s that affected Philadelphia’s growth. The 1720s and 1730s saw a great influx of immigrants coming from Germany and Northern Ireland to the city and the nearby areas. These new inhabitants developed the region for farming, and Philadelphia exported grains, wood products, and flax seeds to Europe and other American colonies, which helped the city to recover from the depression.

In 1704, the three southernmost counties of Pennsylvania were allowed to break off and become the new semi-autonomous colony of Lower Delaware. New Castle, being the most influential, affluent, and powerful settlement in the new colony, became its capital. After Gustav the Great’s success in Battle of Breitenfeld, Swedish colonists started to settle in the area in the early 17th century, founding the New Sweden colony in what is presently southern New Jersey. With the increase of English colonists and the construction of the port on the Delaware, Philadelphia quickly developed into an important colonial city.

Philadelphia was renowned for its commitment to religious toleration, which drew many other faiths to the city in addition to the Quakers. These included Mennonites, Pietists, Anglicans, Catholics, and Jews, and these groups soon outnumbered the Quakers although still having an influential economic and political presence. Conflict often occurred between and within religious groups, as evidenced by the riots of 1741 and 1742 that arose from high bread prices and drunken sailors, and the 1742 ‘Bloody Election’ riots caused by the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Petty crime was rampant in Philadelphia, and so serving in public office was considered a poor reputation, leading to fines for those who refused the responsibility after being chosen for it. One man even fled the city to avoid being mayor.

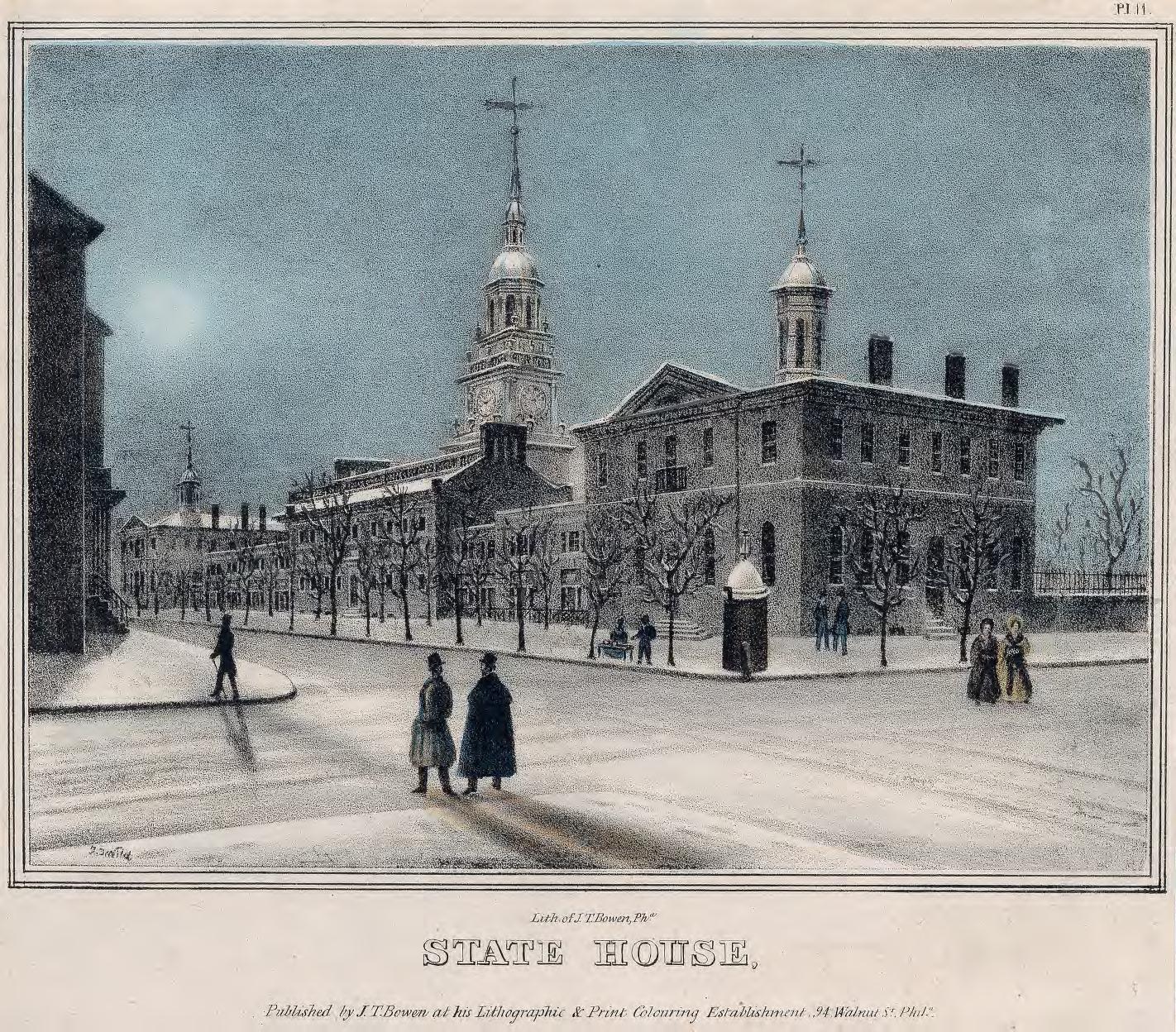

In the 1700s, Philadelphia, like other American cities, had numerous problems with garbage, animals, and unpaved roads. Early efforts to improve life in the city were not successful due to lax enforcement of laws. But, by the middle of the century, the transformation of the city had begun. Christ Church and the Pennsylvania State House, otherwise known as Independence Hall, were constructed. Additionally, streets were paved and lit with oil lamps. The first newspaper in the city, Andrew Bradford’s American Weekly Mercury, was published on December 22, 1719.

In the 1700s, Philadelphia gained a reputation for its cultural and educational developments, partially due to James Logan arriving in the city in 1701 and becoming mayor in the early 1720s. Logan was responsible for creating a library of considerable size, as well as guiding the renowned botanist John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin upon their arrivals. Franklin had a significant role in the city’s protection from fire with the Union Fire Company and he was additionally selected as post master general, connecting Philadelphia to New York, Boston and other locations. Furthermore, he provided funds for the construction of the first hospital, Pennsylvania Hospital, along with the charter of the College of Philadelphia. To protect the city from French and Spanish privateers, Franklin formed a volunteer defense group and constructed two batteries.

The French and Indian War began in 1754, part of the Seven Years’ War, and Franklin recruited militias in response. As a result of the conflict, Philadelphia saw an influx of refugees from the western frontier. This was followed by Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763, which caused refugees to once again enter the city, including Lenape seeking refuge from other Native Americans, who were angered by their lack of violence, and white frontiersmen. The Paxton Boys unsuccessfully attempted to enter Philadelphia to attack, but were prevented by the city’s militia and Franklin, who convinced them to leave.

Philadelphia and the American Revolution

In the mid-1700s, British Parliament’s adoption of the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts, along with other grievances, provoked an upsurge of anger and political tension in the colonies. Residents of Philadelphia joined a boycott of British products. After the Tea Act of 1773, warnings were issued against anybody who would store tea and any vessels that sailed up the Delaware with tea. Following the Boston Tea Party, a shipment of tea arrived on the Polly in December. A committee instructed the captain to leave without offloading his cargo.

In 1774, a succession of acts inflamed the colonies and caused activists to call for a national congress. This was accepted and the First Continental Congress was then organized in September and held in Carpenters’ Hall. During the American Revolutionary War, this hall was the venue of the First and Second Continental Congresses.

In April 1775, the Revolutionary War commenced after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and in May, the Second Continental Congress convened at the Pennsylvania State House. A year later, they came together again to compose and pass the Declaration of Independence in July 1776. Philadelphia was a significant element of the conflict; Robert Morris commented,

In response to George Washington’s loss at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, the citizens of Philadelphia made preparations for the anticipated British Army attack, one of which was to quickly remove the Liberty Bell and other bells from the city and send them to the Zion German Reformed Church in Northampton Town (now Allentown). The Liberty Bell was concealed under the church floorboards during the period of British occupation of Philadelphia, from September 1777 to June 1778. The bell was eventually returned to Philadelphia when the British forces left the city on June 18, 1778.

In 1783, upon the culmination of the Revolution, Philadelphia was designated the provisional capital of the United States between 1790 and 1800, and the city remained a major financial and cultural hub for some years. It was home to a large African American population who assisted runaway slaves and established the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the nation.

The port town was prime for British capture by sea, so officials enlisted soldiers and analyzed potential entry points from Delaware Bay, yet no fortifications or other constructions were created. In March of 1776, two British frigates began blockade of the mouth of Delaware Bay and British troops were marching south from New York through New Jersey. This induced a mass exodus of half the population in December, including the Continental Congress, who moved to Baltimore. George Washington fought against the British progress at the battles of Princeton and Trenton, thus allowing the refugees and Congress to come back. However, in September 1777, the British invaded Philadelphia from the south and Washington encountered them at the Battle of Brandywine, yet he was eventually forced to retreat.

Washington’s defeat at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777 resulted in thousands of Philadelphians fleeing north within Pennsylvania and east into New Jersey. To avoid the British Army seizing the Liberty Bell and other large bells, Congress relocated to Lancaster and then to York. In order to protect the Liberty Bell from being recast into munitions, it was hastily sent north and concealed underneath the floor boards of the Zion German Reformed Church in Northampton Town (now Allentown, Pennsylvania).

On September 23, 1777, as expected, British forces marched into Philadelphia and were welcomed by Loyalist supporters. This occupation of the colonial capital lasted for a period of ten months. After the French became involved in the war on the side of the Continentals, the British troops departed Philadelphia on June 18, 1778, in order to defend New York City. On the same day, the Continentals reclaimed Philadelphia, with Major General Benedict Arnold being appointed as the city’s military commander. The city’s government arrived a week later, and the Continental Congress returned in early July. After the British retreat from Philadelphia on June 18, 1778, the Liberty Bell, which had been hidden in an Allentown church since September 1777, was returned to Philadelphia.

At the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War, many Patriots who had served in the conflict had yet to receive payment for their work. Congress disregarded the veterans’ demand that they be paid. This led to the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 in which these unpaid soldiers marched with arms to the Pennsylvania statehouse in Philadelphia. Unable to cover the cost, Congress and their families relocated to Princeton, New Jersey, thus leaving the city of Philadelphia virtually deserted.

The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 caused Congress to move out of Philadelphia and settle in New York City, which was made the provisional capital. After the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Philadelphia was no longer the focus of American politics. An agreement among Congress was made to construct a new, permanent capital on the Potomac River.

After the end of the Revolutionary War in 1787, Philadelphia’s economy quickly rose. Yet, a yellow fever epidemic in August 1793 caused a major disruption to the city’s development. This epidemic, which lasted four months, was the first of its kind in 30 years and it was believed that the 2,000 refugees who had recently arrived from Saint-Domingue had brought the disease with them. Many residents became scared of getting infected, leading to 20,000 people leaving the city by mid-September and other neighboring towns prohibiting their entry. As a result, trading was nearly halted and Baltimore and New York decided to quarantine people and goods coming from Philadelphia. The fever eventually died down with the onset of colder weather at the end of October and declared over in mid-November, leaving behind a death toll of 4,000 to 5,000 people. Unfortunately, yellow fever outbreaks continued to be a problem for Philadelphia and other major ports during the 19th century, though none of them had as many fatalities as the one in 1793. Another epidemic occurred in 1798, resulting in an estimated 1,292 deaths.

The Pennsylvania Abolition Society defended a state law that abolished slavery in 1780 and required any slaves brought to the city to be freed after six months of residence. From 1796 to present, 500 slaves from Saint-Domingue were granted freedom in the city. Philadelphians and residents of the Upper South were concerned that free people of color may inspire slave insurrections in the United States.

Gary B. Nash, a historian, has highlighted the influence of the working class and their animosity to the elite in the northern ports. He argues that artisans and craftsmen, forming a radical element in Philadelphia, assumed control of the city from around 1770 and enforced a Democratic form of government throughout the revolution. This group maintained power by enlisting the assistance of the local militia to propagate their beliefs to the working class and stayed in control until the upper class rebelled. Inflation in Philadelphia was problematic, with the poor being unable to purchase necessities. This led to unrest in 1779, with the public blaming the wealthy and Loyalists. In January, a riot of sailors demanding higher wages resulted in the destruction of ships. On October 4, the Fort Wilson Riot saw people attack James Wilson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, who was speculated to be a Loyalist sympathizer. Soldiers put an end to the riot, though 5 people were killed and 17 injured.

In 1790, Philadelphia was decided upon as the temporary capital of the United States, and the United States Congress established in March 1789 fully occupied the Philadelphia County Courthouse, which was later named Congress Hall. The Supreme Court worked at City Hall, and Robert Morris donated his 6th and Market Street home to serve as a residence for President Washington, now known as the President’s House.

During the 10 year period that Philadelphia served as the federal capital, members of Congress were exempt from the abolition law, however, those within the executive and judicial branches, including President Washington and Vice-President Jefferson, were not. The two aforementioned leaders brought slaves with them as domestic servants and managed to get around the law by frequently relocating them from the city before the 6 month mark. Two of Washington’s slaves were able to escape from the President’s House, and Washington eventually replaced those that were lost with German immigrants, who were indentured servants.54

In 1799, the Pennsylvania state government relocated from Philadelphia, and the US government followed suit in 1800. At the time, the city was one of the most active ports in the nation and the largest city with a population of 67,787 people living in the city and its surrounding suburbs. Unfortunately, the Embargo Act of 1807 and then the War of 1812 put a strain on Philadelphia’s maritime trade, and it never returned to its pre-embargo status, with New York City taking its place as the busiest port and largest city.

Philadelphia Changes in the 19th Century

Between the mid and late 1850s, immigrants from Ireland and Germany poured into Philadelphia and its suburbs, increasing the population . As the affluent moved west of the 7th Street, the less privileged were forced to move into the former homes of the upper class, which were converted into tenements and boarding houses. These areas were surrounded by hundreds of small rowhouses and filled with garbage and a disgusting smell of animal pens. In the 1840s and 1850s, hundreds of people died annually due to diseases such as malaria, smallpox, tuburculosis and cholera, attributed to the lack of sanitation; the poor were victims of the most fatalities. Small rowhouses and tenement housing were built south of South Street

Philadelphia Was Still Wild

Serious violence was a major issue; gangs such as the Moyamensing Killers and the Blood Tubs had control over several parts of the city. In the 1840s and early 1850s, when fire companies, some of which were infiltrated by gangs, attended a fire, disputes between the companies would emerge. The lawless behavior of the fire companies was mostly put to an end in 1853 and 1854 when the city took a more authoritative role. During this time period, violence was also aimed at immigrants out of fear for job competition and resentment towards their religion and ethnicity. Nativists held meetings mainly based on anti-Catholic and anti-Irish views, and assaults were conducted against immigrants, the most severe being the Philadelphia nativist riots of 1844. African Americans were also targeted during the 1830s, 40s, and 50s; these individuals were seen as competition for jobs and resulted in race riots that caused the burning of African-American homes and churches. Joseph Sturge commented in 1841 that he believed there was no other city in the world that had a greater hatred of colored people than Philadelphia. Several anti-slavery societies were created, and free blacks, Quakers, and other abolitionists ran safe houses as part of the Underground Railroad. However, working class and ethnic whites opposed the abolitionist movement.

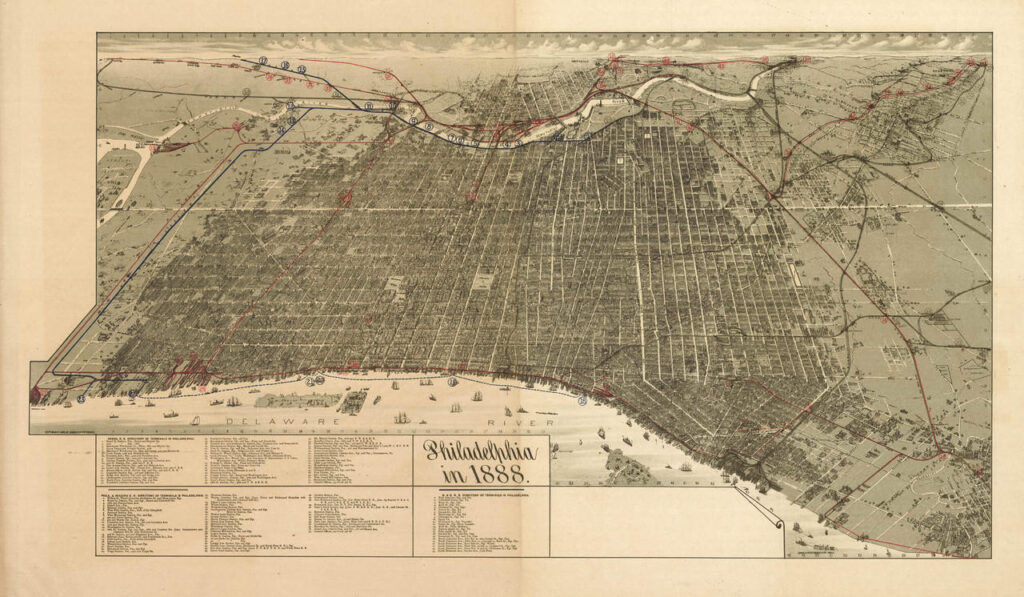

Due to the lack of control over the lawlessness and the residential growth north of Philadelphia, the Act of Consolidation in 1854 was passed on February 2. This act made the boundaries of Philadelphia to be the same as the boundaries of Philadelphia County and included various subdistricts within that county.

The Civil War And Philadelphia

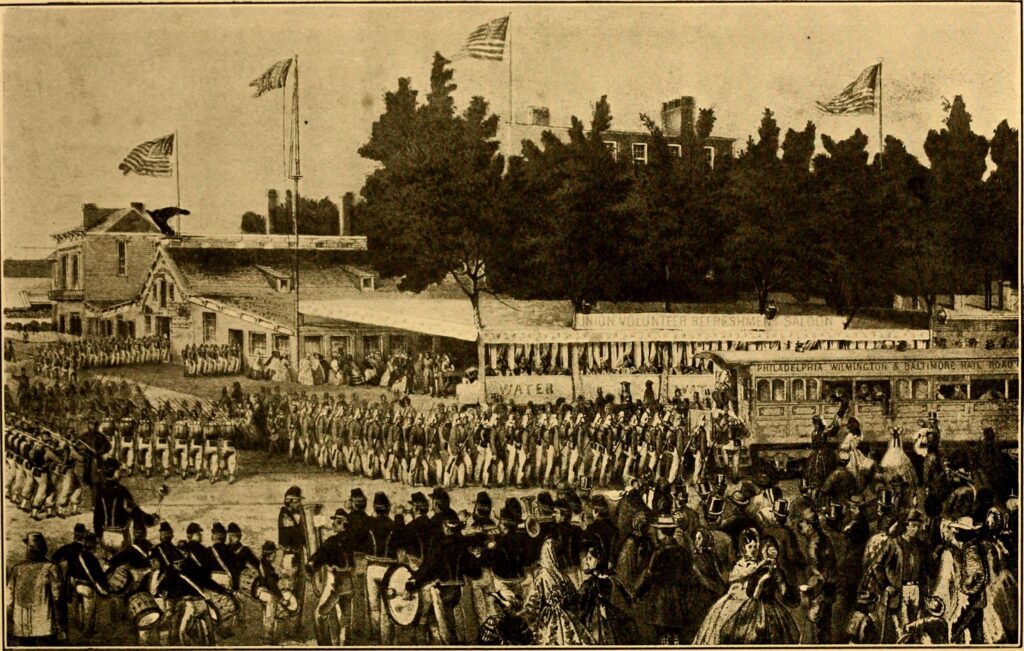

Once the Civil War started in 1861, the attitude of Philadelphia people toward the South changed. Hostility was directed to those who sympathized with the Confederacy. People in mobs went to the houses of those suspected to support the South and to the headquarters of a secessionist newspaper. The police and Mayor Alexander Henry were able to keep them away. The city itself provided soldiers, ammunition, and warships to the Union army, and the local factories produced uniforms for the Union. Furthermore, Philadelphia was a major place to care for the wounded, with 157,000 soldiers and sailors being treated in the city. In 1863, the city was preparing for a potential invasion by the Confederate Army, but Union forces successfully repelled them at Gettysburg.

In the years following the US Civil War, Philadelphia’s population expanded significantly. In 1860, it was 565,529 people, increasing to 674,022 by 1870 and reaching 817,000 by 1876. The increase in population was occurring not only along the Delaware River, but also across the Schuylkill River. The largest contributor to the growth was immigration, in particular from Ireland and Germany. In 1870, 27% of the population was foreign-born.

In the 1880s, immigrants from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Italy began to outnumber those from Western Europe, with many of the former group being Jewish. By 1905, the population of Jews in Philadelphia had risen from 5,000 to 100,000. The Italian population grew from 300 in 1870 to 18,000 in 1900, with most settling in South Philadelphia. African Americans from the South also migrated to Philadelphia, making it the largest northern U.S. city for this demographic by 1876, with nearly 25,000 individuals. By 1890, the number of African American residents had increased to 40,000. At the same time, the city’s upper class began to move out to the suburbs, facilitated by newly constructed railway lines, particularly along the Philadelphia Main Line.

Politically, the Republican Party held sway in the city, with a strong political machine based around the Gas Trust. The trust was able to command contracts and awards for their cronies, and the police department was reorganized. In 1895, compulsory school legislation was passed, and the Public School Reorganization Act freed education from the control of the political machine. University of Pennsylvania moved to West Philadelphia and was restructured; Temple University, Drexel University and the Free Library were also established during this time.

The metropolis of Philadelphia was occupied with organizing and hosting the Centennial Exposition, which was the very first World’s Fair held in the United States, celebrating the nation’s Centennial. It was held in the Fairmount Park, and included displays of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone and the Corliss Steam Engine. From May 10, 1876, to November 10, of the same year, more than nine million people attended the fair. Subsequently, the city began to build a new City Hall, which was intended to reflect its new ambitions. Although the project was plagued with corruption, it was eventually finished after twenty-three years. Upon completion of its tower in 1894, City Hall, was the tallest building in Philadelphia, a status it maintained until One Liberty Place exceeded it in height in 1986.

During the era, Philadelphia was home to some of the most prominent industries of the time such as the Baldwin Locomotive Works, William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company, and the Pennsylvania Railroad. The westward expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad aided Philadelphia in competing with New York City for domestic commerce in the transportation of iron and coal resources from Pennsylvania. The other local railroad was the Reading Railroad, but it went bankrupt and was taken over by New Yorkers. The Panic of 1873, which was caused by the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia bank Jay Cooke and Company, and the depression of the 1890s, hindered the economic growth of Philadelphia. Despite these difficult times, the city’s various industries such as iron and steel, textiles, cigar, sugar, and oil, allowed it to survive. The major department stores in the city, such as Wanamaker’s, Gimbels, Strawbridge and Clothier, and Lit Brothers, then developed along Market Street.

At the close of the century, Philadelphia had developed nine public swimming pools, making it a pioneer in the US.

Philadelphia was one of the early industrial hubs in the United States, its major industry being textiles. There were strong economic and familial links to the South, with many planters having second homes there and maintaining business relations with banks. Several of these individuals sent their daughters to French finishing schools supervised by refugees from Saint-Domingue in Haiti, and they sold their cotton to the textile manufacturers who, in turn, sold some of their products to the South, such as clothing for slaves. At the start of the American Civil War, many citizens in the city were sympathetic to the South, but the majority of the population eventually took a Union stance as the war progressed.

After the American Civil War, the Republican Party was in control of the city government and established a political machine that used patronage to gain influence. By the beginning of the 20th century, Philadelphia was known to be “corrupt and contented”. As reform efforts started to take place, a new city charter of 1950 granted more power to the mayor and weakened the Philadelphia City Council. During the Great Depression, the population began to show support for the Democratic Party of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This party has now been the dominant political force in the city for many decades.

At the end of the 19th and start of the 20th centuries, the population of the city dramatically increased due to immigration from Ireland, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe and Asia. Additionally, the Great Migration of African Americans from rural Southern states and the arrivals of Puerto Ricans from the Caribbean were further attracted to the city’s industrial job opportunities. The Pennsylvania Railroad alone employed 10,000 workers from the South, and many other manufacturing plants and the U.S. Navy Yard employed thousands of industrial laborers along the rivers. The city also grew as a center for finance, publishing, and universities.

Philadelphia’s Growth in the 20th Century

The embargo and decrease in foreign trade caused the creation of local factories and foundries to produce goods that were no longer being imported, thus making Philadelphia a major industrial center. The construction of new roads, canals, and railroads furthered the city’s growth in the industrial sector, while an increase in wages and the ten-hour workday were won by workers in the city in the first general strike in North America. Philadelphia was also the financial center of the country, with numerous banks, the first and second Banks of the United States, Mechanics National Bank, and the first U.S. Mint. Cultural institutions such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Athenaeum, and the Franklin Institute were also developed in the 19th century. The Free School Law of 1834 passed by the Pennsylvania General Assembly created the public school system.

At the start of the 20th century, Philadelphia gained a negative connotation. People inside and outside the city commented that it was stagnant and unwilling to change. Harper’s Magazine reported that “being new or different from what has been is the single thing that is unacceptable in Philadelphia.” In his ground-breaking work of urban sociology The Philadelphia Negro, W. E. B. Du Bois noted that “hardly any other large cities have as bad a record when it comes to mismanagement as that of Philadelphia.”Du Bois’s study discovered that aside from mismanagement and disregard, there were also extreme racial disparities in terms of employment, housing, health, education, and the justice system. These disparities were still present; for instance, between 1910 and 1920, the rate of tuberculosis among black citizens of Philadelphia was four to six times higher compared to that of whites.

Philadelphia was associated with an image of “dullness” and poor governance practices, as well as a reputation for political corruption. The Republican-controlled political machine, under the direction of Israel Durham, had a hand in almost every aspect of city government. It was estimated that US$5 million was lost annually through graft in the city’s infrastructure programs. In spite of the fact that the majority of citizens were Republicans, voting frauds and bribes were still a common occurrence. In 1905, reforms such as personal voter registration and the implementation of primaries for all city offices were put in place. However, the political bosses still managed to remain in control. After Durham’s retirement in 1907, James McNichol took his place, but only had authority in North Philadelphia. Meanwhile, in South Philadelphia, the Vare brothers, George, Edwin, and William, created their own organization. With no centralized power, Senator Boies Penrose assumed control. In 1910, a reform candidate, Rudolph Blankenburg, won the mayoral election, as a result of the internal conflicts between McNichol and the Vares. During his term, Blankenburg made cuts to city costs and increased the quality of services, yet he served only one term. Afterwards, the machine once again took the reins.

In the year 1910, a general strike spread across Philadelphia, beginning with streetcar workers and eventually involving 65,000 to 70,000 people, effectively immobilizing the city.

Reformers in Woodrow Wilson’s administration reunited with the Republican Party, and the reform movement was temporarily stalled during WWI. This changed in 1917 after the murder of George Eppley, a police officer defending a City Council primary candidate, reignited the reformers. They passed laws to reduce the City Council from two houses to one and give the members annual salaries. With the deaths of McNichol and Penrose, William Vare became the city’s political boss. During the 1920s, public flouting of Prohibition laws, mob violence, and police involvement in illegal activities reached a peak, and Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick appointed Smedley Butler of the U.S. Marine Corps as director of public safety. Butler attempted to crack down on bars and speakeasies, but he was unsuccessful and left after two years. The grand jury investigation into the city’s mob violence and other crimes in 1928 resulted in numerous police officers being dismissed or arrested, but nothing changed. Al Smith’s strong support among some residents during his presidential campaign marked the city’s turning away from the Republican Party.

Immigrants coming from Eastern Europe and Italy, as well as African American migrants from the South, contributed to the growth of Philadelphia.This influx of individuals was temporarily halted during World War I, as the factories in the city, including the new U.S. Naval Yard at Hog Island, sought laborers to help with the war effort. This, in turn, prompted the Great Migration. In September 1918, the influenza pandemic was reported at the Naval Yard, and its spread was exacerbated by the Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade, which drew in more than 200,000 people. Mortality rates escalated, leading to the death of 12,000 people by the end of October.

The developing fame of cars brought about the expansion of streets, for example, the Northeast (Roosevelt) Boulevard in 1914, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 1918, and the Benjamin Franklin Bridge to New Jersey in 1926. Additionally, numerous streets were changed to one-way avenues in the early 1920s. It was during this period that Philadelphia started to modernize. Steel and concrete skyscrapers were built, old structures were wired for power, and the city’s first commercial radio station was established. In 1907, the city opened the first subway and held the Sesqui-Centennial Exposition in South Philadelphia. Furthermore, the Philadelphia Museum of Art was opened in 1928.

In the three years after the stock market crash of 1929, 50 banks in Philadelphia closed, with only two of them being large, Albert M. Greenfield’s Bankers Trust Company and the Franklin Trust Company. In the same period, savings and loan associations also had difficulty, with 19,000 mortgaged properties being foreclosed in 1932. By 1934, 1,600 of the 3,400 associations had shut down. Manufacturing, factory payrolls, and retail sales in the region all decreased significantly between 1929 and 1933, with construction payrolls dropping by 84 percent. Unemployment was at its highest in 1933, with 11.5 percent for whites, 16.2 percent for African Americans, and 19.1 percent for foreign-born whites being unemployed. Mayor J. Hampton Moore blamed the economic struggles on people’s laziness and wastefulness, not the Great Depression. His successor, S. Davis Wilson, instituted many programs funded by the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, despite having opposed the program during his campaign. In 1936, 40,000 people in Philadelphia were employed under the WPA program.

In Philadelphia, the state government and labor’s formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) sparked a union-friendly atmosphere. Nevertheless, African Americans were blocked from certain labor advancements, leading to several strikes in the textile unions. By the 1930s, the Democratic Party started to gain more traction in the city, driven by the leadership of the Roosevelt administration during the Depression. This was demonstrated by the Independent Democratic Committee engaging with citizens and the Democratic National Convention being held in the city in 1936. Voters in Philadelphia strongly supported Democratic candidates, including Franklin D. Roosevelt for president, and Congressmen and state representatives. Despite this, Republicans still remained in control of city government, albeit with smaller majorities.

At the start of WW2 in Europe, and the danger of the U.S. getting involved, resulted in a growth of jobs in defense-related industries. When the U.S. joined the war in 1941, Philadelphia started to mobilize. The city consistently met war bond quotas and, by the time the war was over in 1945, 183,850 residents had been in the military. This labor shortage meant that businesses and industries had to hire women and workers from outside Philadelphia. In 1944, the Philadelphia Transportation Company promoted African Americans to the roles of motormen and conductors, which had previously been inaccessible to them. This upset other PTC workers, causing them to go on strike and paralyzing the city. In response, President Roosevelt sent in troops to get the workers back, which occurred six days later after the federal ultimatum.

At the conclusion of World War II, Philadelphia faced a dire housing shortage. The majority of homes in the city had been built in the 19th century and many were in a state of disrepair, with inadequate sanitary facilities and overcrowded conditions. The competition for housing between African Americans who had moved to the city from the South as part of the Great Migration and Puerto Ricans led to racial conflict. Concurrently, the wealthier, typically white, middle-class residents of Philadelphia moved out to the suburbs in what came to be known as white flight.

During the 1950s, the population of Philadelphia had reached a peak of more than two million people, only to start to decrease afterwards. The suburban counties, on the other hand, experienced population growth. This prompted some residents to move away from the region. This was due to the restructuring of industry that caused tens of thousands of job losses in the city. Philadelphia lost five percent of its population in the 1950s, three percent in the 1960s and more than thirteen percent in the 1970s. The manufacturing and other major businesses that had supported middle-class lives for the working class were in decline, with many leaving the area or shutting down in industrial restructuring, which included major declines in railroads.

The city spurred on construction projects near University City in West Philadelphia and the area around Temple University in North Philadelphia. In the process, the Chinese Wall elevated railway was taken down and the development of Market Street East around the transportation hub was implemented. Moreover, gentrification saw a number of historical neighborhoods such as Society Hill, Rittenhouse Square, Queen Village, and the Fairmount area restored. To advance the image of Philadelphia, a non-profit organization called Action Philadelphia was organized. Furthermore, the airport grew, the Schuylkill Expressway and the Delaware Expressway (Interstate 95) were constructed, Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) was established, and residential and industrial development happened in Northeast Philadelphia.

In the 1950s, a great deal of Philadelphia’s housing had become outdated and of substandard quality. After WW2, the construction of highways and the suburbanization of families seeking newer dwellings led to a decrease in the city’s population. This, combined with the economic restructuring of the mid 20th century and the thousands of job losses, resulted in poverty and social displacement. From the mid 20th century to the early 21st century, the city was beset by gang and mafia violence.

By the end of the 20th century and the start of the 21st, historic neighborhoods experienced a renewal and gentrification that attracted a larger middle-class population. Moreover, immigrants from Southeast Asia, Central and South America also put in much effort to make the city more vibrant. In the 90s and early 2000s, the city was promoted and incentives were given which made it more attractive and resulted in a condominium boom in Center City and its surrounding areas.

Plans for the United States Bicentennial of 1976 began in 1964. By the early 1970s, three million dollars had been contributed, yet no definitive plans were drawn up. As a result, the planning group was restructured and a variety of citywide activities were scheduled. The Independence National Historical Park was restored, and Penn’s Landing was finished. Despite the fact that fewer people arrived than what was anticipated, the event had a positive effect on the city’s aura, resulting in an array of yearly neighborhood festivals and fairs.

In 1947, the Democratic Party chose Richardson Dilworth as their candidate for mayor, but he ultimately lost to the incumbent, Bernard Samuel. During his campaign, Dilworth pointed out the corruption in the city government. As a result, the City Council established a committee to investigate the charges. This investigation, and the findings it produced, gained attention from around the country. It was eventually discovered that $40 million of city funds were unaccounted for, and that the president judge of the Court of Common Pleas had manipulated court cases. The fire marshal was sent to prison, while an official in the tax collection office, a water department employee, a plumbing inspector, and the head of the police vice squad all committed suicide after the criminal discoveries were revealed. The public and the media called for reform, which led to the drafting of a new city charter by the end of 1950. This new charter gave more power to the mayor, while weakening the authority of the City Council. The council was made up of ten members elected by district, along with seven members elected at large. Additionally, the city’s administration was restructured, and new boards and commissions were created.

In 1951, Joseph S. Clark was the first Democrat mayor to be elected in 80 years. He filled administrative positions with those who were qualified and worked to eliminate corruption. Although Clark’s reforms were in effect, a powerful Democratic patronage organization replaced the former Republican one. Richardson Dilworth followed in Clark’s footsteps before resigning to run for governor in 1962. James Tate, the city council president, became the first Irish Catholic mayor when he was elected in 1963. He was reelected in 1967 despite opposition from reformers who deemed him to be an organization insider.

In the 1960s, Philadelphia experienced the same civil unrest as the rest of the United States. Civil rights and anti-war protests, led by Marie Hicks in an effort to desegregate Girard College, took place in the city. Students held a sit-in at the Community College of Philadelphia. Race-riots broke out in Holmesburg Prison and a 1964 uprising on West Columbia Avenue resulted in two deaths, 300 injuries, and $3 million in losses. As well, crime was a prevalent issue, leading to gang violence related to drugs. In a 1970 survey, the City Planning Commission deemed crime as the city’s primary problem. The court system was overwhelmed and Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo’s tactics were criticized. Despite this, Rizzo is credited with preventing the level of violence seen in other cities at the time and was elected mayor in 1971.

Re-elected in 1975, the controversial Rizzo had his admirers and adversaries. While police, fire, and cultural services flourished, other departments such as the Free Library, Recreation, the City Planning Commission, and the Streets Department had to cut back. In 1972, the radical MOVE organization was formed, and tensions with the city rose. In 1978, a clash at their Powelton Village base resulted in the death of a police officer. Nine MOVE members were sentenced to prison. In 1985, another stand-off occurred at their West Philadelphia headquarters, which was assumed to be inhabited by armed resisters. The police dropped a bomb from a helicopter that started a fire which killed eleven MOVE members and five children, and destroyed sixty-two houses around it. The city was sued in civil court by the survivors and had to pay damages.

During the 1980s, Philadelphia battled with crime, including Mafia warfare in South Philadelphia, drug gangs, and crack houses in the slums. William J. Green was elected mayor in 1980, and W. Wilson Goode became the city’s first African-American mayor in 1984. The city also saw development in Old City and South Street, and modern skyscrapers were built in Center City. Unfortunately, labor contracts signed during the Rizzo administration created a financial crisis that Green and Goode couldn’t prevent, and the city was close to bankruptcy by the end of the decade.

The bombing of MOVE in the Cobbs Creek area of Philadelphia by city helicopters in 1985 resulted in the deaths of 11 people and the destruction of 61 homes.

After the conclusion of the Laotian Civil War in the 1970s, which was linked to the Vietnam War, a group of Hmong refugees found a home in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, they were subject to discriminatory acts, which prompted the city’s Commission on Human Relations to hold hearings. According to Anne Fadiman, author of The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, lower-class citizens were angered by the fact that the Hmong were granted $100,000 for employment assistance when they themselves were out of work. Consequently, by 1984, three quarters of the Hmong people had relocated to other cities in the United States. Vietnamese and other Asian immigrants have settled in the city, particularly around the Italian Market area. Additionally, numerous Hispanic immigrants from Central and South America have moved to North Philadelphia.

In 1992, Ed Rendell was voted in as Philadelphia’s first Jewish mayor. During this time, the city had numerous outstanding debts, the lowest bond rating of the fifty largest cities in the US, and a budget deficit of US$250 million. Rendell was able to attract investment to the city, balance the budget, and even generate small surpluses. Renewal of various parts of the city continued into the 90s, with the opening of a new convention center in 1993, as well as seventeen new hotels by 2000. Tourism was a priority, with heritage tourism and festivals being held to attract visitors. In 2005, National Geographic Traveler called Philadelphia “America’s Next Great City”, highlighting its reawakening and urban layout.

Philadelphia Marches into the 21st Century

John F. Street, the former president of the city council, was elected mayor in 1999, initiating a period of city revitalization. The Street administration focused on the city’s most impoverished neighborhoods and made considerable progress. Tax breaks enacted in 1997 and 2000 sparked a condominium boom in Center City, and the population of the area increased to 88,000 in 2005, representing a 24 percent rise in households from 2000.

In the 1990s, the City of Philadelphia faced a series of controversies within the police department, including the underreporting of crime. Furthermore, accusations arose that contracts were awarded based on campaign donations for Street’s 2003 mayoral reelection. In the early 2000s, a rise in violent crime followed a period of decline in the 1990s. In 2006, the murder rate in Philadelphia was 27.8 per 100,000 inhabitants compared to 18.9 in 2002.

During the excavation for a new Liberty Bell Center, the ruins of the President’s House were uncovered. This led to a series of archeological works in 2007. Ten years later, in 2010, a memorial was opened on the site to honor George Washington’s slaves, African Americans in Philadelphia, and U.S. history. This memorial also marks the location of the former house.

In 2008, Michael Nutter, a business professional, was elected as Philadelphia’s third African-American mayor. During his time in office from 2007 to 2009, the city saw a 30% decrease in crime rate. Nutter also implemented the Foreclosure Prevention Program to assist residents with their housing, and other cities have since copied the initiative.

In 2015, Pope Francis made a stop in Philadelphia during his U.S. tour. He was there for the 2015 World Meeting of Families and celebrated mass for one million attendees on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

The tourism sector has become a major contributor to Philadelphia’s economy, with the city being ranked as the 8th most visited place in the United States in 2018.